Since I joined the Church in 1972, I have been categorized by my fellow-members as cursed, less-valiant, fence sitter, Cain’s lineage, and others that would be too impolite to be repeated here, but that’s part of the legacy, if you will, or I will call it more of a burden that members of black African ancestry have had to deal with. And notice, I’m from Brazil—I’m talking about my experiences in Brazil also, not just in the United States in the last sixteen years.

This statement was related by Marcus H. Martins, the first man of black African descent to serve a mission for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints after the 1978 revelation that lifted a ban on black men holding the priesthood and black men and women attending the temple in the Church. Brother Martins has also served as chair of the Department of Religious Education at BYU-Hawaii, as a bishop, stake high councilor, a temple officiator, a translator of the Book of Mormon, and most recently as mission president of the Brazil São Paulo North Mission. Notably, he is the son of Helvécio Martins, the first Latter-day Saint of African descent to serve as an LDS Church general authority.[1]

Marcus H. Martins’s experience is certainly not unique and his situation has been one of the struggles that Mormonism has dealt with during is history. The priesthood ban was in place for well over one hundred years with unclear reasons for its existence. Since the reasons for initiating this ban have not been clarified, there has been and still is a tendency to attempt to explain the policy, especially with the speculative suggestions garnered from American culture or developed within Mormon theology by previous Church leaders. Included in these suggestions, as Martins stated, were the beliefs that blacks had been cursed with black skin and ineligibility to hold the priesthood because of wicked ancestors or because they had been less-valiant in the pre-mortal existence—beliefs that have lingered to this day. I remember one time in my own life, as a priest, when the adult advisor for us 17-year olds got all excited to teach us a lesson about the premortal existence. He bounded up, grinning from ear to ear as usual, and said “I’ve been doing lots of reading, and I have some great stuff to share,” and he did. For the most part, it was an excellent lesson. Then, suddenly, he pulled out a quote from some obscure seventy back in the 1950s that said that we were blessed according to how we had lived in the premortal existence, and we must have been pretty awesome to have been born into the One True Church, as opposed to the blacks who were denied the priesthood because they were all less-faithful prior to being born. I was disturbed to hear that you could classify who had been good and who had been evil in a prior life based on their skin color—it smacked of racism—and I said, “That doesn’t seem right. I don’t think that’s what we believe any more.” The advisor threw up his arms and said (still smiling), “Hey, I’m just quoting the Brethren.” At that time I hadn’t been given the tools to analyze such things and still believed everything a General Authority said must be true, so I grudgingly backed off and slumped down in my seat for the rest of the lesson.

The next day, I was carpooling with another quorum member to high school and asked him why he hadn’t said anything about it as well. He responded that it just seemed like such an obviously wrong quote that it was a dead issue to him. The fact of the matter is, however, that these pseudo-doctrinal beliefs are not a dead issue, but are still something that haunts the Church today and are only slowly being resolved. Only two years ago, BYU professor Randy Bott was quoted in a national news article as stating that blacks were descendants of Cain and were barred from the priesthood because of that connection. The article also referenced the less faithful in premortality idea my priest quorum advisor passed on to us. It went on to quote Bott as saying, “God has always been discriminatory” when it comes to whom he grants the authority of the priesthood and blacks were like “young child prematurely asking for the keys to her father’s car” in seeking the priesthood prior to the ban’s lifting because they “were not yet ready for the priesthood” and it would not have benefited them. In fact, the article states that, “Bott says that the denial of the priesthood to blacks on Earth — although not in the afterlife — protected them from the lowest rungs of hell reserved for people who abuse their priesthood powers…. So, in reality the blacks not having the priesthood was the greatest blessing God could give them.”[3]

The curse of Cain and the less-valency theories of the priesthood ban are still sometimes taught in Sunday Schools and other church settings today.

Most of the beliefs that Dr. Bott taught were previously taught by other members of the Church, some of them in very high positions. This has been problematic in the Church’s efforts to reach out to African Americans—one study found that an important reason for a low retention rate among African Americans was the “continuing undercurrent of racism in such LDS popular beliefs as the curse of Cain” and that “surveys of Mormons… demonstrated clearly that the religious hostility implied in those old myths played an important part in generating anti-black prejudice and discrimination.”[4] This has not been a problem just for people of African descent, however—a 2011 survey focused on understanding Mormon disbelief found that the Church’s stance on race issues was among the top eight most important general factors in why people who previously believed in Mormonism came to stop believing in the Church.[5] In the past, the Church seems to have chosen to let time filter these beliefs out of our culture, with mixed results. More recently, however, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has released a statement that summarizes what is known about the history of the ban and has disavowed the traditional explanations for the ban and posted it on LDS.org.

This statement, released at the beginning of December 2013, indicates that the Church’s belief system today does not support racism in any form, but points out that the American society that the Church was founded in was racist, and that although Joseph Smith opposed slavery and allowed blacks to be ordained, in 1852 Brigham Young publically announced a policy of not allowing men of black African descent to be ordained to the priesthood. The new Church statement went on to review institutional racism in American government and put President/Governor Young’s policy in the context of the political and social situation of the Utah Territory of the time. Included in this section was some discussion of the idea that black Africans were cursed to be slaves and to be banned from the priesthood due to descent from Cain or Ham. A brief review of the ban’s history between President Young’s leadership and the 1978 revelation that lifted it followed. The conclusion of the statement focused on a straightforward disavowing of past statements of church leaders and theologians that supported the ban, including the idea of a cursed lineage, premortal failures, racial inferiority, and the idea that mixed-race marriages are a sin.[6]

The statement is very significant if only for the statements about the pseudo-doctrinal beliefs that once supported the policy. As stated in the new document, during President Brigham Young’s tenure:

The justifications for this [priesthood] restriction echoed the widespread ideas about racial inferiority that had been used to argue for the legalization of black “servitude” in the Territory of Utah. According to one view, which had been promulgated in the United States from at least the 1730s, blacks descended from the same lineage as the biblical Cain, who slew his brother Abel. Those who accepted this view believed that God‘s “curse” on Cain was the mark of a dark skin. Black servitude was sometimes viewed as a second curse placed upon Noah‘s grandson Canaan as a result of Ham‘s indiscretion toward his father.[7]

After the restriction was in place,

The curse of Cain was often put forward as justification for the priesthood and temple restrictions. Around the turn of the century, another explanation gained currency: blacks were said to have been less than fully valiant in the premortal battle against Lucifer and, as a consequence, were restricted from priesthood and temple blessings.[8]

Third, many Church leaders consistently taught that interracial marriage was a sin. In one extreme example, President Brigham Young stated that, “Shall I tell you the law of God in regard to the African race? If the white man who belongs to the chosen seed mixes his blood with the seed of Cain, the penalty, under the law of God, is death on the spot. This will always be so.” (JD 10:110.)

All these beliefs hung in the air after the ban was lifted in the late 1970s, questionably applicable but still widely believed. The press release went out from Church headquarters with instructions “to get the widest possible dissemination of the full text of the latter but to offer no explanations or commentary,”[9] indicating that there was to be no statements about what the official position on beliefs related to the ban. The tension and confusion over whether we were to continue to believe in the teachings that had previously been given about black Africans is displayed in what is probably the most widely-published public discussion of the revelation that lifted the priesthood ban. In this address to CES instructors, Elder Bruce R. McConkie told his audience to:

Forget everything that I have said, or what President Brigham Young or President George Q. Cannon or whomsoever has said in days past that is contrary to the present revelation. We spoke with a limited understanding and without the light and knowledge that now has come into the world….

It doesn’t make a particle of difference what anybody ever said about the Negro matter before the first day of June of this year, 1978. It is a new day and a new arrangement, and the Lord has now given the revelation that sheds light out into the world on this subject. As to any slivers of light or any particles of darkness of the past, we forget about them.[10]

This statement has been celebrated and used by proponents of discarding the pseudo-doctrinal beliefs for years, but on closer examination, we see that Bruce R. McConkie was only referring to the fact that blacks could be ordained, contrary to previous policy, and not necessarily anything else. In the very same sermon, he stated that “we do not envision the whole reason and purpose behind all of it [the priesthood ban]; we can only suppose and reason that it is on the basis of our premortal devotion and faith” and referred to blacks at one point in the printed edition of his address as “the seed of Cain and Ham and Egyptus and Pharaoh,”[11] with similar statements being published in subsequent printings of McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine after the revelation was given. This would indicate that he still continued to believe and to teach the old rationales for the ban.

At the same time, other apostles and prophets spoke differently. In 1978, Spencer W. Kimball said that, “‘Mormonism no longer holds to… a theory’ that blacks had been denied the priesthood ‘because they somehow failed God during their pre-existence.’ ”[12] Ten years later, Elder Dallin H. Oaks stated in a news interview that:

It’s not the pattern of the Lord to give reasons. We [mortals] can put reason to revelation. We can put reasons to commandments. When we do so, we’re on our own…. Some people put reasons to the one we’re talking about here [the priesthood ban], and they turned out to be spectacularly wrong….

I’m referring to reasons given by general authorities and reasons elaborated upon… by others. The whole set of reasons seemed to me to be unnecessary risk taking…. The reasons turn out to be man-made to a great extent.[13]

These statements, however, were not widely publicized, leaving a large amount of uncertainty as to what members were to believe or not to believe. Further, when President Gordon B. Hinckley was asked about the issue in the 1990s, he reportedly stated that the 1978 Revelation “continues to speak for itself” and that, “I don’t see anything further that we need to do.”[2] He seems to have honestly felt that the issue was resolved, stating on yet another occasion that, “I know that we’ve rectified whatever may have appeared to be wrong at that time [the pre-1978 period].”[20]

Confusion continued to exist, however. As one commentator observed in the late 1990s:

I suspect most members assume that the 1978 revelation is similar to the Manifesto: it is a change in practice only, and does not affect the underlying doctrine. So just as we apparently still believe in plural marriage in heaven, we seem bound to accept the ultimate inferiority of the black race. The church’s silence on this issue loudly supports the assumption that the change has been in practice only, not theory.

I believe that, for historical, doctrinal, moral, and practical reasons, the church needs to officially and emphatically repudiate the pre-1978 rationalizations for withholding priesthood ordinations from blacks.[14]

A few members with similar views, headed by a black Saint named A. David Jackson, set about submitting an appeal to the Church officials during the late 1990s, with the support and help of Elder Marlin K. Jensen of the Seventy. They approached the Church through legitimate channels, requested that a firm declaration that repudiated any racist statements made in the past be added to the Doctrine and Covenants, since Mormons believe that “almost anything said by a General Authority is quasi-scripture and inspired…. Hence, the absence of any official correcting statement by the Church regarding these issues will perpetuate a belief system in these unfortunate and pejorative views.”[15] In 1998, however, Jackson told Larry Stammer of the Los Angeles Times about this effort in hopes of accelerating the process. Armand Mauss—a sociologist who was involved in writing the statement—had warned him that such action would simply “derail the whole campaign.” When asked by reporters about the Stammer story after it was printed, he simply stated that “Jackson and Stammer had killed any chance for such a formal statement of repudiation to occur” and noted in his autobiography that, “I turned out to be quite right about that, of course, as President Hinckley, himself badgered by the Utah press, finally declared that he had heard nothing about plans for a repudiation, and none such would be forthcoming, nor did he regard it as necessary.”[16]

Jackson and company are not the only concerned Saints who have tried to petition the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints to repudiate the doctrines taught about race. Some have even pushed for an outright apology for these doctrines and priesthood policy. Darron Smith, a black member who was released from teaching at BYU in part due to his outspokenness on this matter has written that,

Our goal is to get the Mormon Church to apologize for its racist actions and teachings, just as other faith-based traditions have apologized. This is necessary is to disprove the prevailing notion that God “had His reasons” why humans denigrated and discriminated against other human beings based on race. When the Church refuses to give an apology, it leaves its millions of members left to question whether this was really God’s will rather than human racist actions. A recent online survey revealed that the majority of Mormons no longer believe that Blacks were cursed, but most of them still continued to hear these teachings in their church. Black Mormon members in the survey overwhelmingly asked for a public, unambiguous apology.

Like most of us, I’m hoping to leave this world a better place for our children. I am not cursed. And I certainly don’t want my children growing up thinking or even hearing that they were cursed. Please join me in asking the Mormon Church to issue an official, public apology for their role in racism.[17]

Hopefully, from the statements above, one can get a feel for why this issue has been a problem. Essentially, Mormon teachings for many years systematically taught that people with black African ancestry were denied privileges in the Church because they had evil ancestors and that their spirits were the most wicked or at least indecisive spirits in a prior existence. Further, it was taught that they were not to mix with whites in marriage and parenthood. A believe that such men and women as Martin Luther King, Jr., Nelson Mandela, Jane Manning James, or Elijah Ables were inherently less righteous than white men such as Adolf Hitler, Joseph Stalin, and any other wicked person of Caucasian lineage based on their ancestry and skin color is a disturbing idea to many people—particularly people who are of black African descent themselves. But, as has been argued, because of a belief in a semi-infallible leadership, it would take a statement from the Church leadership to truly undo these beliefs among the Mormons.

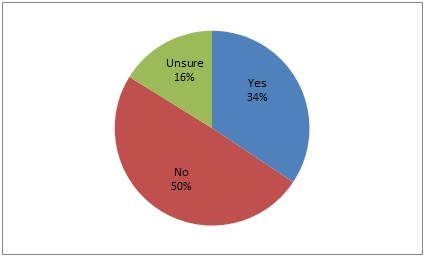

I was interested in finding out how true this was, and so, as part of an online survey I was administering for a study of what people believed about the priesthood ban, I asked a couple of questions about these pseudo-doctrinal beliefs. There were 106 respondents, most of whom were probably white Caucasians living in the western United States. The results were interesting, and although they are not conclusive, are at least suggestive of general beliefs among North American Mormons. Of those who were asked, “Do you think Africans were denied the priesthood because of Do you think Africans were denied the priesthood because of certain ancestors (i.e. Cain, Ham, Canaan, Egyptus)?” only a third of respondents replied yes, with another 16% were unsure. It’s understandable for this to have a decently strong following, since this belief has been the strongest rationale for the ban from day one. Yet, even before the recent statement was released, 50-66% of the people who took my survey didn’t think that this was the reason for the ban (Figure 1). The other pertinent question I asked was, “Do you think that Blacks were denied the priesthood because they were less-faithful in the premortal existence?” The results were even more dramatic: less than 7% responded “yes” or “unsure” (Figure 2). I have talked with my peers (mostly Utah Mormons in their 20s) about this belief, and generally have drawn strong reactions against it. All of this would seem to indicate that the salutary neglect of these doctrines did allow them to atrophy to some extent, though not completely. It will be interesting to see how much these statistics will shift with this new Church statement in the coming months and years.

Figure 1: Do you think Africans were denied the priesthood because of Do you think Africans were denied the priesthood because of certain ancestors (i.e. Cain, Ham, Canaan, Egyptus)?

Figure 2: Do you think that Blacks were denied the priesthood because they were less-faithful in the premortal existence?

In recent years, the Church has released a series of statements about the ban, including, significantly, an introduction to the Official Declaration 2 in the 2013 edition of the LDS scriptures. All three prior to the latest one have used similar language, admitting that, “Early in its history, Church leaders stopped conferring the priesthood on black males of African descent. Church records offer no clear insights into the origins of this practice.”[18] They have generally disavowed racism and stated that traditional statements about the ban’s reasons are not our current explanation, but have not gotten into specifics. This new statement, however, has gone into specifics:

Over time, Church leaders and members advanced many theories to explain the priesthood and temple restrictions. None of these explanations is accepted today as the official doctrine of the Church….

Today, the Church disavows the theories advanced in the past that black skin is a sign of divine disfavor or curse, or that it reflects actions in a premortal life; that mixed-race marriages are a sin; or that blacks or people of any other race or ethnicity are inferior in any way to anyone else. Church leaders today unequivocally condemn all racism, past and present, in any form.…

The Church proclaims that redemption through Jesus Christ is available to the entire human family on the conditions God has prescribed. It affirms that God is ―no respecter of persons‖24 and emphatically declares that anyone who is righteous—regardless of race—is favored of Him.

With this being said, it is well to remember the example of President Joseph Fielding Smith, who previous to the experience that will be related below was probably the single most significant exponent of the racial doctrines now disavowed by the Church. Eugene England—a BYU professor and important figure in the more liberal Mormon circles—met with Joseph Fielding Smith to ask him about these beliefs. In Eugene England’s own words, this is what happened:

It came to my attention that Joseph Fielding Smith (then President of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles) had published an article in the Church News about this matter and in the process had essentially contradicted one of his assumptions in his earlier discussion of the matter in The Way to Perfection, then calling blacks an ”inferior” race and now specifically saying they were not. Two of my friends who were concerned about the same matter, and, as I did, looked at President Smith as the nearly official scriptorian of the Church, made an appointment for us to see him. President Smith was not very anxious to see us since he was being baited from many sources at that time, but after some assurances of our intentions he gave us some time and was particularly gracious when one of my friends, moved I think by the prayer we offered together before going, began the interview by confessing in tears that his original motives for coming had been somewhat contentious. I told President Smith about my experiences with the issue of blacks and the priesthood and asked him whether I must believe in the pre-existence doctrine to have good standing in the Church. His answer was, “Yes, because that is the teaching of the Scriptures.” I asked President Smith if he would show me the teaching in the Scriptures (with some trepidation, because I was convinced that if anyone in the world could show me he could). He read over with me the modern scriptural sources and then, after some reflection, said something to me that fully revealed the formidable integrity which characterized his whole life: “No, you do not have to believe that Negroes are denied the priesthood because of the pre-existence. I have always assumed that because it was what I was taught, and it made sense, but you don’t have to to be in good standing because it is not definitely stated in the scriptures. And I have received no revelation on the matter.”[19]

The ability to acknowledge when we are wrong and to make room for change in belief, such as President Smith did here is important in building a more constructive future. Hopefully, we will be able to fully discard these disavowed pseudo-doctrinal beliefs and make it so that Marcus H. Martin’s experiences will no longer be repeated within the LDS community. It may take time to get there, but this new statement provides the tools necessary to achieve that condition.

[1] Marcus H. Martins, “A Black Man in Zion—Reflections on Race in the Restored Gospel,” 2006 FAIR Conference, Best of Fair Podcast, accessed 15 Jan 2014.

[2] Richard N. Ostling and Joan K. Ostling, Mormon America (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1999), 104.

[3] http://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/the-genesis-of-a-churchs-stand-on-race/2012/02/22/gIQAQZXyfR_story.html?tid=pm_politics_pop. Accessed 13 Sept 2013.

[4] Armand L. Mauss, “ ‘Casting off the Curse of Cain’: The Extent and Limits of Progress since 1978”, in Black and Mormon, Newell G. Bringhurst and Darron T. Smith, ed. (Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2004), 86.

[5] “Understanding Mormon Disbelief,” www. WhyMormons Question.org, March 2012, 8.

[6] “Race and the Priesthood.” LDS.org topics, Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Web. Accessed 15 January 2014.

[7] “Race and the Priesthood.”

[8] “Race and the Priesthood.”

[9] Edward L. Kimball, “Spencer W. Kimball and the Revelation on the Priesthood,” BYU Studies 47, no. 2 (2008), 67.

[10] Bruce R. McConkie, “All Are Alike Unto God,” 18 August 1978, BYU Speeches.

[11] See Bruce R. McConkie, “The New Revelation on Priesthood,” in Priesthood (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1981), pp. 126-37, esp. p. 128.

[12] Cited in Kimball Lengthen Your Stride 238.

[13] Cited in Dallin H. Oaks, Life’s Lessons Learned (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book Co., 2011), 68-69.

[14] Keith E. Norman, “The Mark of the Curse: Lingering Racism in Mormon Doctrine?” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought, 32 no. 1, (1999), 124.

[15] Richard N. Ostling and Joan K. Ostling, Mormon America: The Power and the Promise, (New York: HarperCollins, 1999), 103-104.

[16] Armand Mauss, Shifting Borders and a Tattered Passport: Intellectual Journeys of a Mormon Academic, (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2012), 109.

[17] Darron Smith, “The Mormon Church: Issue an Official Apology for Racist Teachings that Declared Blacks Cursed,” darronsmith.com, 29 October 2012. Accessed 12 Jan 2014.

[18] Official Declaration 2 in Doctrine and Covenants; “Church Statement Regarding ‘Washington Post’ Article on Race and the Church,” Mormon Newsroom, February 29, 2012, accessed November 21, 2013, http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/racial-remarks-in-washington-post-article; “Race and the Church: All Are Alike Unto God,” Mormon Newsroom, accessed November 21, 2013, http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/race-church.

[19] Eugene England, “The Mormon Cross,” Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought 8, no. 1, 83-84.

Great piece. I too had taken the time to read Bruce R’s words for myself because the folklore is that he had disavowed everything that he said in the past. Well low and behold once you read the statement (Bruce R”s) that’s not the case. People need to take the time to read the articles that are footnoted in the “Race and the Priesthood” statement to gain a better understanding of what happened. They (Church Leadership) need to apologize. Waiting for GC to see if that happens. I would like to be proven wrong, but if past actions are an indication (quietly posting “Race and the Priesthood” to an obscure “topics” section of the Church website as opposed to placing it above the fold on the LDS.org homepage where it belonged), I think that the leadership of the church is ill equipped to deal with this.

I wanted to post a few thoughts and hope someone can answer my question at the end. So, a few thoughts first.

1) There are scriptural statements that indicate that there were varying degrees of faithfulness in the pre-mortal world and that at least for some individuals, that affected their access to the Priesthood in mortality. Alma 13 specifically mentions certain individuals earning the right to the High Priesthood due to their faith in the pre mortal world. Where as others were not afforded the same blessing due to not being as faithful. Faithfulness in the pre-mortal world enabled certain individuals to be given leadership positions both in the pre-mortal world and in mortality (Abraham 3, D&C 138). Many of these “leadership” positions are also “priesthood positions.” I think it’s reasonable to say that the Lord considers pre-mortal faithfulness as one of the considerations for mortal access to the Priesthood. Those who were faithful enough, are “reserved” to come forth in accordance with D&C 138. A person foreordained to receive the priesthood would not be sent to the earth to a nation that did not have the priesthood among them. So there seems to be a connection between pre-mortal faithfulness and mortal conditions (ie. lineage, nation of birth, time of birth, circumstances etc). That doesn’t mean being born into a lineage banned from the priesthood makes you unfaithful in the pre-mortal world. God sends righteous souls to all nations to perform works to bring out his purposes. But it would be untrue to say the scriptures don’t support the connection of pre mortal faithfulness and priesthood access. There is a connection.

2) God has consistently made lineage a factor in extending Priesthood blessings. In effect, bans on the Priesthood based on lineage seems characteristic of God’s plan to save His family. Only one example is needed – during Christ’s mortal ministry, Christ did not extend priesthood to any other lineage other than Israelites. That excludes a majority of God’s children. It was later extended to Gentiles only when the decree was given by God.

3) The policy of Priesthood bans has changed from time to time in accordance with God’s will. Sometimes there has been different policies in different places at the same time. EG. Only Levites in Israel and non-Levites in America during the same period. A righteous, worthy person of the wrong lineage would be banned from the Priesthood in one country and not another. After the flood there is no record anywhere of non-Shemites having the Priesthood.

4) In ancient times, God could create an effective priesthood ban without any official decree. As families once had the gospel (at least from Noah), once they fell into apostasy, God choosing not to send the gospel to them means that lineage is effectively banned until he does. Many nations have had thousands live and die under an effective priesthood ban.

5) Has God cursed” or “blessed” any lineage as to the priesthood? Yes, if you think “cursed” means you can’t have it in mortality and blessed means you can. It seems more common for God to restrict access to the Priesthood than to have it universally available. But no one is “cursed” in the sense that progression towards exaltation is ultimately prevented or that certain of God’s children are predestined to fail or have their progression stunted. Looking at pre-mortal, mortal and post-mortal existence as a whole existence- all of God’s children can progress to exaltation based on their own choices.

6) It seems to me that it’s a reasonable conclusion that priesthood bans based on race is normative for God. That concept seems to connect in some part to faithfulness in the pre mortal world, in the sense that at least those foreordained to receive the priesthood and fulfil priesthood duties on earth would not be born at a time, nation, family circumstances of lineage that would prevent that blessing being possible. Bans by race also connects with the idea that priesthood bans is often based on the choices of an ancestor, not the individual banned from the priesthood. Ham’s descendants banned from the actions of Ham. Further, there is scriptural foundations for the idea that the Africans come from the lineage so banned. Or at least that they do not come from the lineage promised the priesthood. The only family we have a record of having a “promise” of the priesthood is Abraham’s seed, namely Israel. So if not “banned”, there appears to at least be no “promise”.

7) Is there any evidence that Brigham Young was not moved upon by the Spirit to ban Africans from the Priesthood? If policies change from time to time, why not from 1852 to 1978? He did say that he felt that in the future the ban would come to an end, indicating that did not think that Africans would never have full access to the gospel, but that they should for a certain period of time. I know David O McKay considered ending the Priesthood ban but felt impressed not to. It seems as though he also thought it was a temporary ban and was more questioning IF it was time to end it not whether it was be ended at some point. Spencer W Kimball and members of the Quorum of the 12 considered ending the ban for some time and prayed many times that it would be ended – but did not act until God gave them the green light. They also phrased the question “whether it was time”, not “should there be a ban?” Or “is the ban wrong and we need to correct a mistake?” This consistency in the understanding of the prophets seems to reveal that they did not know all the reason for the ban, but wanted to bring it to an end. They just needed a green light from the Lord. Once they did, they actioned that with gusto and never looked back.

8) I agree that there are many false doctrines circulating around the justifications and doctrinal underpinnings of the ban. Were all Africans fence sitters in the pre-mortal world – no. That’s far too simplistic. It’s like saying all Chinese are bad drivers. Racism is about reducing complex situations down to easy to grasp boxes, so that judgements can be made easier and life can be predictable. Are Africans under the ban not able to progress to exaltation? That’s a stupid one. Anyone who contends this does not understand the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. The list of falsehoods goes on. But to say that banning a lineage from the Priesthood during certain times and in certain places is doctrinally wrong is also a false doctrine. Reducing the ban down to the racism or ignorance of church leaders is possibly overly simplistic as the racist’s world view is also. Assuming Brigham Young was a racist or misunderstood God’s will, he may still have put the ban in place due to being commanded to by God. A racist David O McKay could have left it in place because he was commanded to by God. Spencer W Kimball may not have been correcting a mistake, but as prophets before him seeking the Lord’s will on when to end the ban – judging that they wished it could end but recognising it wan’t their decision to make.

THE QUESTION

So my question is a) Is there any reason to say the ban was not doctrinally correct? Is this priesthood ban in our day outside the principles we can deduce from the scriptures of other proscriptive or effectual bans? (I’ve outlined a few above, but not all the principles I’ve gleaned from the scriptures on why and how God bans the priesthood). b) If the ban can be doctrinally supported, is any evidence that God did NOT put the ban in place during 1852 – 1978? Ie. It wasn’t a mistake, or an omission.

If something is doctrinally supportable and the Prophet says it needs to happen, then even if I don’t understand it, or the prophet doesn’t explain why, I need to support it and no apology is required if in the future the policy is changed for any reason. The “mistakes” the church talks about may not be that the ban was in place. But other mistakes in how they dealt with that ban, justified the ban, or any number of things. The fact that certain doctrines are not the “official” doctrine of the church does not mean that they aren’t true. It’s true that the Book of Mormon happened in America and someone has the right theory about where. But the Church takes no position. That’s not to say all theories are wrong. Just that the Church does not need to explain where the Book of Mormon happened for the book to be true. The Church may likewise not need to explain any doctrine or practise that people want to question. I’ve read nothing that makes me conclude the ban has no doctrinal basis and was a mistake. Neither that God did not want the ban in place. So keen to hear if anyone has any view points otherwise.

Devoted LDS,

Thank you for your thoughtful comment and questions. You made a lot of very good points and I agree with you on many things. Before I respond directly to your question and statements, I want to restate what I understand you are saying and I also want to state briefly my stance and purpose for writing this blog post.

I understand that you are saying that there is scriptural precedent for a priesthood ban based on ancestry and race and that there is still room to believe the ban was divinely inspired during the time it was in place in the LDS Church. There may even be room for the traditional defenses of the ban to be true in some cases, though not all–that would be an oversimplification. Correct me if I’m wrong, but that is what I understood you were saying.

My purpose and goal for writing this post was to say that we simply don’t know why the ban was in place and that much of the theology we have often used to defend the ban is probably not true and is demeaning to our brothers and sisters of black African ancestry–such as a curse of Cain, or that because Blacks were denied the priesthood, they were all less faithful in the premortal existence. My three main hopes are to prevent those particular doctrines from being taught in the Church, to make Black men and women more welcome and comfortable in Mormonism, and to create openness for diversity in belief. As long as you are not believing and telling Black people that they are less-than, cursed, or evil in any way because of skin colour, premortal choices, or ancestry, I am quite fine with any opinion on the ban’s origin, especially since there is so little known about it.

As far as your questions posed at the end of you comment, I personally believe that there is evidence on both sides of the issue. There is plenty of scriptural precedent of denying certain groups of humans the priesthood, either explicitly or implicitly, as you have pointed out. I would be leery of using the word race for most of these cases, since Israelites were not racially different than Levites (or even many of their closely-related neighbors, such as Moabites, Edomites, Ammonites, etc.) and they were not allowed to hold the priesthood because of choices made during Moses’s ministry. It is not always clear, as well, about how the priesthood was banned and why. For example, you mention Ham. The only curse put on Ham’s son Canaan that we have explicit record of is slavery to Israel, not a priesthood ban. We do have a reference in the Book of Abraham that Pharaoh in Egypt was a righteous man, a grandson of Ham, but cursed by Noah as pertaining to the priesthood and that he was ” of that lineage by which he could not have the right of Priesthood.” (Abraham 1:26-27.) Thus, there is some sort of curse on Pharaoh (not Ham, specifically) for priesthood, and he was denied the priesthood because of lineage. It could be because of Hamic ancestry, as Mormons have traditionally assumed, but there are other explanations available. For example, Hugh Nibley said it could be because he was a descendant of Ham through a daughter and priesthood only descended through male lines. Also, we don’t know for sure who all were descendants of Ham or how truly universal the flood was. Since Ham was cursed with slavery to Israel, whichever group that nations believing in an Abrahamic faith (Judaism, Christianity, Islam) have enslaved have often historically been relegated the role of being descendants of Ham in the belief system of the slave owners. Since Africans became the main slaves to European countries, they began to be considered the descendants of Ham, though that is not necessarily the case. Consider also Facsimile 3 in the Book of Abraham, in which Pharaoh (the man cursed as pertaining to the priesthood) is white, while a servant in the facsimile (on who we have no scriptural statements on priesthood eligibility) is black. Nor were all descendants of Egyptians banned in the priesthood. For example, Nathan–the prophet that sealed King David to his wives–had an Egyptian grandfather (see 1 Chronicles 2:34-37). Likewise, Joseph of Egypt and Abraham both seem to have married some Egyptian women. My point is to say, again, that while we have precedent, we don’t know all the reasons or modes of operation for the ban in the past or present.

As far as your points on the premortal existence, yes, those foreordained are put in a place to receive the priesthood, and those unworthy probably won’t be placed in a position to receive the priesthood. However, the whole process of both fore-ordination and situations in life is probably an incredibly complex mix of choices of individuals and other people affecting each other, the preparations that were made, and the needs of both individuals and the people they may influence. It is completely possible that less-worthy people are placed in a situation in life where they receive the priesthood because that is what will help them grow the most while someone who is totally worthy is denied the priesthood by life situation because that is what help them grow the most. So, in brief answer to question a, yes there is doctrine and scriptural history that can be used as solid precedent for the priesthood ban, however, it may not be in the way we think and we need to be cautious in how we use those to defend the ban.

As far as question b, there is, of course, evidence, both doctrinal and historical, that can (emphasis on can) be used to say the ban was not inspired of God, just as there is evidence that can be used to say it did come from God, as you have presented. If that was not the case, this question would not be an issue. I don’t have time to go into this at this moment, though some good reading is the BYU Studies article on Spencer W. Kimball and the ban that the official Church statement my blog post is about links to (either on the side or footnotes, can’t remember) and Russell Stevenson’s book Black Mormon: The Story of Elijah Ables. Both weigh both sides fairly well, and the latter offers what is currently the best conclusion of the origin of the ban that can be reached from historical data currently available. To summarize a few of the key points that can be used, 1: Black men were ordained to the priesthood and allowed to attend the Kirtland temple during Joseph Smith’s presidency. All data that we have indicates that Joseph planned to let blacks attend the Nauvoo Temple if he had lived to see its completion. 2) By extension, if even one man with black African ancestry was ordained, and if he was allowed to hold the priesthood to the end of his life (such as did Elijah Ables, who died during John Taylor’s presidency, and whose descendants were also ordained), then is it logically possible to stay with statements that anyone with a drop of black blood in them could not hold the priesthood? As Paul Reeve observed, “If even one black Mormon was eligible for the priesthood before 1978, then all blacks were.” (see http://www.juvenileinstructor.org/guest-post-professor-bott-elijah-abel-and-a-plea-from-the-past/). 3. There is evidence that Brigham Young had both doctrinal reasons in his worldview (i.e. the racist doctrines carried over from justifying slavery) as well as political ones (slaveholders in Utah, trying to win some support for Utah in the South, fear of repeating problems that occurred in Missouri, etc.) that could be used to support the ban, which have since been discarded, rendering it understandable that he initiated the ban, but not necessarily defendable. 4. Spencer W. Kimball did admit that the ban might be a mistake on at least one occasion prior to the ban being lifted (I don’t have the reference right on hand, but it is in the Teachings of Spencer W. Kimball book). 5. God is no respecter of persons and invites all to come unto Him. He also teaches in the scriptures that the sins of the parents cannot be answered upon the heads of the children.

Again, I feel that there is evidence to believe it either way and am okay with belief that the ban was divinely inspired–you have certainly brought up some valid points to that side of belief. It is both doctrinally and historically defendable and attackable. You asked, however, if there was any evidence that the ban was not divinely inspired, so I share the above. The subject is so complex and difficult to navigate, and there is not enough data to come to a definitive conclusion.

Hey there, I really appreciate your response. I’ve sought answers on all kinds of challenging matters and found my testimony strengthened not weakened. I love your approach and intent. It’s because of really thoughtful and well studied people like yourself that the general membership can gain answers and I appreciate that. Thank you. I respect and agree with many of your points of view. I would like to share 2 thoughts. 1) Being cursed is also being covenanted with. 2) Inconsistency between Joseph and Brigham.

BEING CURSED

I also come from a lineage that in some regards can be considered “cursed”. I am a descendant of the “Lamanites” – which is not a racial term, but a spiritual term for any of the lineages mentioned in the Book of Mormon that did not remain faithful (whether they were originally Nephites, Ishmaelites, Mulekites or any other lineage not specifically mentioned in the book of Mormon). In particular, I am from the lineage of Joseph. I say this is a “cursed” lineage, because God said through Nephi, if any of the groups in America rejected His counsels a curse would come upon them and they would not be given the gospel until the latter days, when a remnant of Joseph (from another branch) would restore the gospel and then the gospel would flourish amongst all branches of Joseph throughout the world. Further scriptures add that this latter day tribe of Joseph would be key in the spreading of the gospel to all nations. After my ancestors rejected the gospel, many generations lived and died without the gospel being preached amongst them or priesthood blessings extended. In that regard, my ancestors were cursed for hundreds of years because of their unrighteousness. Even those who would have accepted the gospel if was extended were effectively banned until they could be taught it in the post-mortal world and recieve their ordinances (most likely in the millennium through temple work).

So while being of a cursed lineage, I am also from a covenant lineage. I can’t think of any other people that have their covenants expressed in scripture than descendants of Joseph. And I can see the fulfilment of these covenants in my own life in a very powerful way.

My opinion is that if the African line is similarly cursed, they are also similarly covenanted with. We don’t have the scriptures recording these covenants, as I do for my ancestors in the Bible and Book of Mormon. But I’m sure God has a divine plan to rescue all lineages cursed to not have the gospel and extend blessings to them in his own time and in accordance with justice and mercy. I don’t feel my ancestors were “cursed” in the sense that it limits their self worth as a child of God, or limits their potential to achieve exaltation (although it does delay certain milestones of exaltation, such as temple sealing). But my ancestors were none-the-less cursed and much work needs to be done to extend salvation to them through temple work. So I would say, yes, Africans, among almost of all God’s children were at some time “cursed” and suffered many generations without the gospel until they as a people were prepared for the gospel again. God chose when, where and how he would restore a cursed people to a covenant relationship with him.

I think the scriptures teach a number of principles for how God deals with “cursed” lineages. Much of it sounds racist when viewed in relation to one group of people. But when looked at as a pattern of God’s dealings with families of the earth, it’s just and merciful.

INCONSISTENCY BETWEEN JOSEPH & BRIGHAM?

When Joseph first revealed the doctrine of temple baptisms, the people practised them with no thought for policy, until Joseph Smith recieved further counsel on the matter. Restrictions were put in place, such as baptisms can only happen in temples, with recorders and witnesses etc. Why did God not reveal all of that to Joseph up front – like a Handbook of Instructions for temple work?

This pattern of policies changing, extending, becoming officially declared over time – particularly by Brigham Young in Utah after Joseph’s death, is possibly applicable here. Brigham could have been putting in place something that Joseph did not regulate (in the same way as Joseph did not regulate temple baptisms at first). Perhaps that further light came to Brigham with regards to priesthood blessings, at the same time as Brigham also announced publicly to the church plural marriage, the doctrine of sealing to ancestors. It seems as though once Brigham got to Utah he had the chance to regulate, particularly with regards to how temple blessings are extended to the living and the dead. Perhaps the ban came as part of him deeply considering how to regulate the church generally and the priesthood ban was part of that process that Joseph did not deal with.

Love to have any further thoughts and I hope I’m not being disrespectful in my thoughts, as opposed to fixed opinions. The use of the term “cursed” seems offensive, but it’s only because this is the word used in this context and is not intended to hurt feelings.

That is a unique and pleasant view of being cursed. I appreciate your thoughtful approach and I do agree with you that seeking for answers to challenging questions and concerns has strengthened my faith in many ways, though it has produced a more nuanced and mature form of faith than I experienced in my youth. When put into the context and understanding you have placed it in it isn’t as offensive to me. It might be pointed out that Caucasians like myself were also cursed in similar regard until the days of Peter, as have virtually every people and group on earth at some time or another. I guess, again, my point was ultimately to push against stating that anyone is less-than because of race. As far as regulations, that is a good point and one that could very well be the case. I’m not going to stake my life on it, but it’s a possibility. Again, thank you.

Love you brother. I’ve not sounded out loud these thoughts before. But was interested to see your thoughts. Thanks