The attitude of Mormons towards government is paradoxical. Mormonism has beliefs that encourage support for governments, yet also a history of conflict with the United States Government. In addition, there are some Mormon doctrines that deemphasize the need for government that are held in tension with pro-government beliefs. This tension was manifested in nineteenth century Utah’s continual conflicts with the United States. It has also surfaced more recently in the worldview of individuals such as Ezra Taft Benson and Cliven Bundy. At its core, this paradox is rooted in the conflict born of a people who believe that the Constitution of the United States of America is inspired of God suffering from intolerance and corruption in the United States of America.

The Scannel Daguerreotype: a purported photograph of the Prophet Joseph Smith. No one know or has been able to prove either way whether or not this is a photograph of Joseph Smith

The Prophet Joseph Smith believed that governmental forms should be respected, especially the Constitution of the United States of America. A section of Doctrine of Covenants outlined the basic attitude of Mormons towards governments by stating that: “We believe that all men are bound to sustain and uphold the respective governments in which they reside, while protected in their inherent and inalienable rights by the laws of such governments.”[1] In particular, Joseph Smith held the form of government in the United States in high regard. For example, one revelation he produced in December 1833 stated that God had “established the constitution of this Land by the hands of wise men.”[2] Joseph Smith’s feelings about the Constitution are, perhaps, summarized best in an 1839 letter where Joseph Smith called the Constitution “a glorious standard” that “is founded in the wisdom of God.” He concluded this letter by testifying that “the constitution of the united States is true” while stating that many of the things that Mormons hold most dear—God, the Bible, the Book of Mormon, the Doctrine and Covenants, Christ, and ministering angels—were all true.[3]

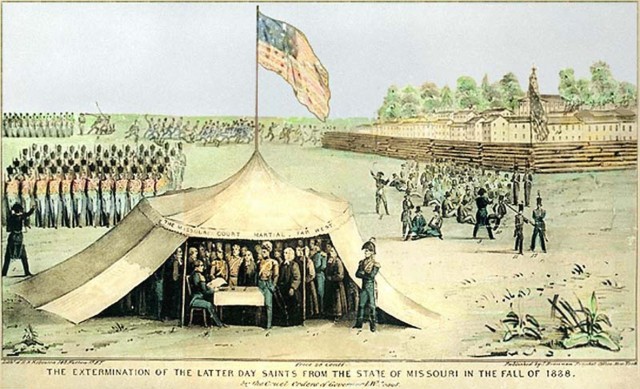

Encounters with mob violence in Missouri and Illinois and a lack of government intervention, however, soured Mormon perceptions of the United States government. From the start, Mormons suffered intolerance and persecution and moved from New York to the Ohio to Missouri and back to Illinois as a result. Joseph Smith lamented that Mormons were “persecuted on account of <our> religious faith—in a country the constitution of which guarantees to every man the indefeasible right to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience.”[4] During the Missouri War, Joseph Smith expressed hope that “the good sense of the majority of the people, and their respect for the constitution, would have put down any spirit of persecution,” but to no avail.[5] In 1840, Joseph Smith petitioned politicians in Washington D.C. to help the Mormons who had been driven from Missouri under the governor’s extermination order, but was rebuffed by President Martin Van Buren, while the Judiciary Committee merely referred them back to the hostile Missouri courts for redress.[6] This caused considerable resentment among the Mormons. President Brigham Young stated later that: “The government of the United States looked on the scenes of robbing, driving, and murdering of this people and said nothing about the matter, but by silence gave sanction to the lawless proceedings.”[7]

Further conflicts with the United States Government and non-Mormons in America led to even greater Mormon disenchantment with government officials. Joseph Smith and his brother Hyrum were killed while in protective custody of the governor of Illinois in 1844. This served to calcify Mormon resentment against their neighbors. One Mormon stated with bitterness that: “The whole nation is accessory to their death, because the murders have boasted thro’ the States of their heroic deeds, and the first one of them has never been punished for committing that murder! And what is more strange, is no man has ever been punished in the United States for killing a Mormon.”[8] Jaded and disillusioned, the Mormons moved westward to the Great Basin region. Their goal for moving west, according to the notes of one 1844 meeting, was to “secure a resting place . . . where we can enjoy the liberty of conscience, guaranteed to us by the Constitution of our Country: rendered doubly sacred by the precious blood of our Fathers, and denied to us by the present authorities, who have smuggled themselves into power in the States and nation.”[9] Mormons felt that they had been denied basic rights by politicians who violated American ideals.

In the West, Mormons faced ongoing struggles with the United States. Mormons desired self-rule so that they could live according to their unique religious principles. The populace in the States felt that Mormons could not be trusted due to their tendency towards theocratic rule, their practice of plural marriage, their socialist programs, and their religious heterodoxy.[10] Because of these issues, mainstream Americans identified Mormonism in terms of a political or social problem, stating that it was an “immoral and quasi-criminal conspiracy” rather than a legitimate religion akin to Protestant Christian denominations.[11] As such, Mormons could (in the minds of Americans) be persecuted and crushed while still upholding the Constitution and American ideals of religious liberty. One Congregationalist reverend wrote: “Mormonism must show that it satisfies the American idea of a church, and a system of religious faith, before it can demand of the nation the protection due to religion. This it cannot do, for it is not a church; it is not religion according to the American idea and the United States constitution.”[12] The tools of the military (the Utah War), the judicial system (the Raid), and politics (the Reed Smoot Hearings) were used to try to force Mormons into submission.[13] As such, Mormon clashes with the federal government simmered for years in Utah.

These conflicts led Mormons to develop a two-fold view in which the U.S. Constitution was supported and admired, but American politicians were not. This was rooted in the tension Mormons faced by holding the form of government in the United States as sacred while suffering persecution that the government participated in, or at least did nothing to stop. One disaffected Mormon claimed that during the Mormon War in Missouri he heard Joseph Smith “in a publick [sic] address, say, that he had a reverence for the Constitution of the United States and of this State, but as for the laws of this state he did not intend to regard them nor care any thing about <them>, as they were made by lawyers and black legs [cheats].”[14] Although drawn from a hostile source, it is similar to what some other Mormon leaders said. For example, after decades of civil disobedience over the issue of plural marriage, President Joseph F. Smith taught that: “The law of the land, which all have no need to break, is that law which is the Constitutional law of the land, and that is as God himself has defined it.” When politicians failed to follow “the provisions of the Constitution,” however, their laws didn’t need to be followed because: “Where is the law human or divine, which binds me, as an individual, to outwardly and openly proclaim my acceptance of their acts?”[15] Perhaps President Brigham Young said it best in 1851 when he quipped: “I love the government and the constitution of the United States, but I do not love the damned rascals who administer the government.”[16]

Despite their conflicts with the U.S. government, Mormons thought of themselves as the true defenders of the American system and ideals. President Brigham Young stated in 1856 that “Utah . . . is the only part of the nation that cares anything about the Constitution.”[17] Further, Joseph Smith believed that Mormons would save the Constitution of the United States from destruction by being “the Staff up[on] which the Nation shall lean and they [the Mormons] shall bear the constitution away from the <very> verge of destruction.”[18] President Brigham Young made a similar prophesy in 1855, when he stated that: “When the Constitution of the United States hangs, as it were, upon a single thread, they will have to call for the ‘Mormon’ Elders to save it from utter destruction; and they will step forth and do it.”[19] Latter-day Saints believed that the United States would one day fail, but that politically-organized Mormons would step into the chaos and preserve a collapsing system.

The apocalyptic worldview of the early Mormons led them to acts that seemed treasonous to other Americans—the organization of their own governmental organizations. In 1844, Joseph Smith organized a group known as the Council of Fifty, which was conceived as the foundation for the “literal kingdom of God” that would “govern men in civil matters,” particularly during the Millennium.[20] Initially, a “Copy of the Constitution of the U S.” was placed in the “hands of a select committee” chosen to design the constitution of this Kingdom of God.[21] This indicates that their intention was to preserve the best aspects of the U.S. Constitution, though with some amendments. In particular, Joseph Smith declared that: “We want to alter it [the Constitution] so as to make it imperative on the officers to enforce the protection of all men in their rights.”[22] Ultimately, they came to advocate a fusion of theocracy and democracy they termed “theodemocracy” in which council itself was the Lord’s constitution and “spokesmen” who would “do as [God] shall command.”[23] For the most part, this council faded out after 1851, but Mormons also organized a “shadow government” known as the State of Deseret that lasted 1862-1870. The State of Deseret was viewed by some as the Kingdom of God that would preserve the Constitution while the remainder of the U.S. collapsed during the Civil War.[24] The United States survived, however, and Mormons eventually abandoned attempts at organizing an ideal government.

Around the turn of the twentieth century, Mormons began focusing on integration into mainstream American society rather than planning for an imminent Millennium. When the railroad was completed in 1869, isolation and complete domination of local politics by the LDS Church became impossible. Increased pressure by the federal government—particularly over the issue of polygamy—led to significant changes in upcoming decades. Plural marriage and dreams of theocracy were discarded and Mormons began to emphasize aspects of their beliefs that blended well with the ideals of Progressive Era America. This led, in part, to Mormons being extremely patriotic Americans. One example of this change is found in the family of Carlos Ashby Badger (1878-1939), a Mormon who was thoroughly involved in politics, particularly as Senator Reed Smoot’s secretary. Badger’s daughter recalled that: “Patriotism and love for our country was an integral part of our lives. We had a big flagpole on our lawn, and we raised the American flag every day.” She added that after they got their first radio: “When the president spoke, of course we would hurry home from school to listen as we were very patriotic. . . . We listened to baseball games—the national pastime, and that was patriotic too.”[25] The Badgers—like many Mormons—had become thoroughly American.

The meeting of the rails at Promontory Point, Utah, marking the completion of the transcontinental railroad and the end of Mormon isolation.

Despite these changes, some Mormons have maintained a level of distrust towards centralized government that is rooted in their theology. In Joseph Smith’s thought, “the mind of man—the intelligent part—is as immortal as, and is coequal with, God Himself.” God “saw proper to institute laws whereby the rest” of the intelligent beings “could have a privilege to advance like Himself.”[26] As such, mankind is free to choose whether or not they will follow those laws that God has put into place and to progress to become more like Him. This idea has often been referred to as free agency or moral agency. Within this worldview, according to one revelation from the Prophet Joseph Smith, the Constitution was considered sacred because it maintained “the rights and protection of all flesh,” which meant “that evry [sic] man may act in doctrine and principle pertaining to futurity according to the moral agency which I [God] have given unto them.”[27] The Constitution was sacred because it preserved moral agency by preventing the government from exercising coercive control over human beings.

Mormon belief in moral agency took on a stronger political dimension during the Cold War. Communism was seen as a system of government that forced individuals to live a certain way whether they willed it or not, while capitalism was seen as a system of moral agency and improvement. A few key individuals such as W. Cleon Skousen and President David O. McKay contributed to this worldview, but Ezra Taft Benson (1899-1994) is perhaps the most notable Mormon Cold Warrior. To Benson, “nothing is more to be prized, nor more sacred, than man’s free choice. Free choice is the essence of free enterprise.” Free enterprise, in turn, is a “dynamo for human betterment” because each individual is motived by self-interest to improve his or her life.[28] In his eyes, governments existed primarily to protect individuals, while welfare programs and redistribution of wealth were coercive and curtailed freedom.[29] He advocated local rule and states’ rights because “great concentration of power is an evil and a dangerous thing.”[30] Due to Benson’s emphasis on the freedom of the human soul, the highest expression of patriotism was to “love America’s traditions and its freedoms” and to fight for them “against all that which threatens them from within as well as from without.”[31]

Ezra Taft Benson

The elements of anti-governmental feelings in Mormonism have been embodied in recent times by Cliven Bundy and his family. The Bundies has been involved in a few high-profile altercations with the federal government over land-use policy in recent years, including the 2014 Bundy Standoff in Nevada and the 2016 occupation of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in Oregon. Like Ezra Taft Benson, Cliven Bundy believes that states’ rights and local rule are important to democracy, going as far as stating that he believes Nevada to be a “sovereign state” or nation and he doesn’t “recognize the United States government as even existing.”[32] Cliven has couched his arguments in terms of patriotism, stating that by standing up to the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), he felt that he was fighting for “freedom and liberty and our Constitution.”[33] Like Joseph Smith and Ezra Taft Benson, Bundy holds the Constitution in high regard, declaring that it is on par with the Bible and Book of Mormon as scripture. [34] At first glance, stating that he doesn’t recognize the federal government yet has great reverence towards the Constitution may seem paradoxical, yet it could be seen as another expression of the Mormon bifurcate view of sacred American governmental ideals but corrupt United States Government. Granted, the Bundy family generally expresses themselves more in terms of American history rather than Mormon theology, but their beliefs do line up well with the anti-government thought of Mormons described above.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints currently takes a more pro-government tact than the Bundy family and like-minded Mormons. During the 2016 Bundy standoff in Oregon, the Church issued a statement about the occupation, stating that Church leaders “strongly condemn” and were “deeply troubled” by the unfolding events. They also went on to affirm that “conflicts with government or private groups can—and should—be settled using peaceful means, according to the laws of the land.”[35] This is in keeping with the Church’s general stance towards governments, as stated in one Church manual—that governments “were instituted of God for the benefit of man.” Church leaders reserve the right to speak out on moral issues, but otherwise the Church remains politically neutral and encourages its members to be involved as citizens.[36]

Mormons have a long and complicated history with government in the United States. Early Mormons like Joseph Smith thought of themselves as patriots who loved the Constitution. Yet, early Mormons were subjected to religious persecution that they felt violated American ideals and developed a cynical view towards the Government of the United States as it failed to protect them. Mormons portrayed themselves as the true heirs of the Constitution, a point of view that helped them transition into being patriotic Americans after they gave up ideals of theodemocracy and the practice of plural marriage at the turn of the twentieth century. During the Cold War, however, renewed skepticism towards centralized governments, such as those found in Communist countries, was encouraged by a few influential Mormons based on the Mormon theology of moral agency. The brand of conservative libertarianism that developed from those ideas have found expression today in a few radical Mormons like Cliven Bundy’s family, though the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints as a whole remain supportive of the government in the United States.

Bibliography

Benson, Ezra Taft. The Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson. Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1988.

Bushman, Richard Lyman. Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, Vintage Books Edition. New York: Vintage Books, 2007.

Church Statement. “Church Responds to Inquiries Regarding Oregon Armed Occupation.” MormonNewsRoom, 4 January 2016, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/church-responds-to-inquiries-regarding-oregon-armed-occupation.

“Discourse, circa 19 July 1840, as Reported by Martha Jane Knowlton Coray [ca. 1850s],” p. [12], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/discourse-circa-19-july-1840-as-reported-by-martha-jane-knowlton-coray-ca-1850s/4.

“Doctrine and Covenants, 1835,” p. 252, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/doctrine-and-covenants-1835/260.

Ford, Rosalia Badger. Rosalia Badger Ford: A Biography. Unpublished manuscript in possession of the author.

Flake, Kathleen. The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004.

Givens, Terryl L. The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy, updated edition. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, 2013.

Grow, Matthew J., Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds. Council of Fifty Minutes, March 1844-January 1846. First volume of the Administrative Records series of The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey. Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016.

“History, circa June–October 1839 [Draft 1],” p. [22], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-circa-june-october-1839-draft-1/22.

Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Larson, Stan. “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text.” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (1978).

“Letter to the Church and Edward Partridge, 20 March 1839–B,” p. 8, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-the-church-and-edward-partridge-20-march-1839-b/8.

Martinez, Michael. “Showdown on the range: Nevada rancher, feds facing off over cattle grazing rights.” CNN 12 April 2014, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/10/us/nevada-rancher-rangers-cattle-showdown/.

Morgan, Dale. The State of Deseret. Logan, UT: Utah State University Press, 1987.

Pulsipher, John. A Mormon Diary as Told by John Pulsipher (1827-1891), 2nd ed. Idyllwild, CA: M3RDPOWER Press, 2006.

“Revelation Book 2,” p. 81, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-book-2/95.

Rogers, Jedediah S. The Council of Fifty: A Documentary History. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2014.

Smith, Joseph, Jr. The Essential Joseph Smith. Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1995.

Smith, Joseph F. Discourse by Joseph F. Smith, April 9, 1882. Journal of Discourses. George D. Watt, G. D., et al (Ed.). 26 vol. Liverpool: F. D. Richards, et al., 1854-1886. 23:69-76.

Strasser, Max. “For Militiamen, the Fight for Cliven Bundy’s Ranch is Far From Over.” Newsweek 2 May 2014, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.newsweek.com/2014/05/02/militiamen-fight-over-cliven-bundys-ranch-far-over-248354.html.

Supulvado, John. “Explainer: The Bundy Militia’s Particular Brand of Mormonism.” OPB 3 January 2016, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.opb.org/news/article/explainer-the-bundy-militias-particular-brand-of-mormonism/.

“The Smoot Case.” Kalamazoo Telegraph (Kalamazoo, MI), 22 April 1904, accessed 2 December 2016, http://c278953.r53.cf1.rackcdn.com/014114.pdf#page=1.

“Transcript of Proceedings, 12–29 November 1838 [State of Missouri v. JS et al. for Treason and Other Crimes],” p. [62], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/transcript-of-proceedings-12-29-november-1838-state-of-missouri-v-js-et-al-for-treason-and-other-crimes/62.

True to the Faith. Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004.

Young, Brigham. Discourse by Brigham Young, February 18, 1855. Journal of Discourses. George D. Watt, G. D., et al (Ed.). 26 vol. Liverpool: F. D. Richards, et al., 1854-1886. 2:279-284.

—. Discourse by Brigham Young, August 31, 1856. Journal of Discourses. George D. Watt, G. D., et al (Ed.). 26 vol. Liverpool: F. D. Richards, et al., 1854-1886. 4:33-42.

[1] “Doctrine and Covenants, 1835,” p. 252, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/doctrine-and-covenants-1835/260.

[2] “Revelation Book 2,” p. 81, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/revelation-book-2/95.

[3] “Letter to the Church and Edward Partridge, 20 March 1839–B,” p. 8, The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/letter-to-the-church-and-edward-partridge-20-march-1839-b/8.

[4] “History, circa June–October 1839 [Draft 1],” p. [22], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/history-circa-june-october-1839-draft-1/22.

[5] Joseph Smith, Jr., The Essential Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1995), 130.

[6] See Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, Vintage Books Edition (New York: Vintage Books, 2007), 396-398.

[7] Journal History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah, 8 August 1851.

[8] A Mormon Diary as Told by John Pulsipher (1827-1891), 2nd ed. (Idyllwild, CA: M3RDPOWER Press, 2006), 7.

[9] Jedediah S. Rogers, The Council of Fifty: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2014), 28.

[10] See Terryl L. Givens, The Viper on the Hearth: Mormons, Myths, and the Construction of Heresy, updated edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997, 2013), 41-65.

[11] “The Smoot Case,” Kalamazoo Telegraph (Kalamazoo, MI), 22 April 1904, accessed 2 December 2016, http://c278953.r53.cf1.rackcdn.com/014114.pdf#page=1. See also Givens, Viper on the Hearth, 11-23.

[12] Reverend A. S. Bailey, “Christian Progress in Utah,” quoted in Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity: The Seating of Senator Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle (Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press, 2004), 22.

[13] See Flake, Politics of American Religious Identity for more information on this subject.

[14] “Transcript of Proceedings, 12–29 November 1838 [State of Missouri v. JS et al. for Treason and Other Crimes],” p. [62], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/transcript-of-proceedings-12-29-november-1838-state-of-missouri-v-js-et-al-for-treason-and-other-crimes/62.

[15] Joseph F. Smith, JD 23:70-71 [9 April 1882].

[16] LDS Journal History, 8 August 1851. The same thought was expressed on 18 February 1855, see Brigham Young, JD 2:182.

[17] Brigham Young, JD 4:40 [31 August 1856].

[18] “Discourse, circa 19 July 1840, as Reported by Martha Jane Knowlton Coray [ca. 1850s],” p. [12], The Joseph Smith Papers, accessed October 7, 2016, http://www.josephsmithpapers.org/paper-summary/discourse-circa-19-july-1840-as-reported-by-martha-jane-knowlton-coray-ca-1850s/4.

[19] Brigham Young, JD 2:182 [18 February 1855].

[20] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in Matthew J. Grow, Ronald K. Esplin, Mark Ashurst-McGee, Gerrit J. Dirkmaat, and Jeffrey D. Mahas, eds., Council of Fifty, Minutes, March 1844-January 1846, first volume of the Administrative Records series of the The Joseph Smith Papers, edited by Ronald K. Esplin, Matthew J. Grow, and Matthew C. Godfrey (Salt Lake City: Church Historian’s Press, 2016), 128.

[21] Cited in Rogers, Council of Fifty, 19.

[22] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 18 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:129.

[23] Council of Fifty, “Record,” 25 April 1844, in JSP, CFM:137.

[24] See Morgan, State of Deseret, 91-119.

[25] Rosalia Badger Ford, Rosalia Badger Ford: A Biography (unpublished manuscript in possession of the author), 4, 7. 14.

[26] Stan Larson, “The King Follett Discourse: A Newly Amalgamated Text,” BYU Studies 18, no. 2 (1978): 11-12.

[27] “Revelation Book 2,” p. 81.

[28] Ezra Taft Benson, The Teachings of Ezra Taft Benson (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1988), 627.

[29] Benson, Teachings, 609, 672-673.

[30] Benson, Teachings, 612.

[31] Benson, Teachings, 591.

[32] Max Strasser, “For Militiamen, the Fight for Cliven Bundy’s Ranch is Far From Over,” Newsweek 2 May 2014, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.newsweek.com/2014/05/02/militiamen-fight-over-cliven-bundys-ranch-far-over-248354.html.

[33] Michael Martinez, “Showdown on the range: Nevada rancher, feds facing off over cattle grazing rights,” CNN 12 April 2014, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2014/04/10/us/nevada-rancher-rangers-cattle-showdown/.

[34] John Supulvado, “Explainer: The Bundy Militia’s Particular Brand of Mormonism,” OPB 3 January 2016, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.opb.org/news/article/explainer-the-bundy-militias-particular-brand-of-mormonism/.

[35] Church Statement, “Church Responds to Inquiries Regarding Oregon Armed Occupation,” MormonNewsRoom, 4 January 2016, accessed 10 October 2016, http://www.mormonnewsroom.org/article/church-responds-to-inquiries-regarding-oregon-armed-occupation.

[36] True to the Faith (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2004), 38-39.